There is an ancient Chinese curse

that says “May you live interesting times.” In fact it’s probably not Chinese,

and probably not ancient, but it certainly describes what we woke up to on

Friday morning: the biggest political shock since 1945 when Labour swept to

power after everyone expected Churchill to win the election, and the biggest political

miscalculation since Eden’s decision to invade Suez in 1956. This is such a significant turn of events

that we can’t shut our eyes to it in church, so I want to reflect theologically

on it this morning . I have to put my cards on the table and say that what I

felt on Friday morning was a mixture of shock, anger, sadness and fear. Shock –

because, although everyone thought the vote would be close, no-one actually

expected it to go this way; anger – because there has been so much

disinformation and downright lying which I believe has deceived people; anger

because nearly half the nation has been pulled unwillingly into a place we

didn’t choose; and fear, because we simply don’t know what will happen now.

Sadness, because any break down of relationships is sad. But I’ve had a couple

of days to reflect and to put my own feelings to one side and to look at where

we find ourselves through biblical lenses.

The three big issues that the

referendum was fought over were immigration, sovereignty, and the economy. What

has been uncovered is the deep division in the UK: between the metropolitan

areas and the rest of the country – London and the rest of England; between

England and Wales and Scotland and Northern Ireland. It seems that the prospect

of the UK splitting apart is again on the table: Scotland away from England and

even Northern Ireland uniting with the Irish Republic. Already there have been

100s of applications in NI for Irish EU passports. Division between young and old, between

middle class and working class, between rich and poor, between the ‘elite’ and

‘the man in the street’. And that has left me chastened to some extent. Because

I have identified so much with the affluent, politically literate metropolitan

population that I have dismissed the very real concerns of those who feel hard

done-by, ignored and trodden over.

What will happen now. Probably

tomorrow petrol prices will rise by 1 or 2p a litre. (I wonder if we will

revert to gallons?) Those with pension and other investments will probably see

their value drop by up to 10%, and those 1000s of UK pensioners who live in the

EU will be harder hit. Those of us who go abroad for a holiday will find it

more expensive. And already EU citizens living here are beginning to wonder if

they are welcome.

A particularly unwelcome reaction

is from ISIS who are rejoicing, according to The Times, over what they see as

the gradual break up of Europe. And Vladimir Putin is reported to be rubbing

his hands in glee at the prospect of a weaker Europe.

But we are where we are; we can’t

go back, and as one German politician has said, “Out is out.” So now we must

look forward with hope and build a new future.

In an article in The Guardian on

Friday the columnist Owen James said that immigration was the prism through

which many people had viewed the referendum. And I think he’s right. Many

working class people have felt overlooked and pushed aside, and helpless to do

anything about what they see as the threat of unlimited immigration, in spite

of the arguments that the majority of immigrants from the EU and elsewhere are

hard-working, tax-paying, law-abiding people. The UK is often described as a

tolerant nation, where people of all races and cultures are welcomed. And maybe

we are, but beneath that there seems to be great fear and resentment. In the

bible God told his people to remember that they were immigrants. Each year at

the harvest festival they were to take their gifts with the words, “My father

was a wandering Aramean” (Deut 26:5). And because they were descended from a

wandering nomad, and because they were a people delivered from slavery they

were to welcome the alien among them. Several times in the psalms it is said

that ‘God watches over the alien’ (Ps 146:9).

Now I think that the British, by and large, are compassionate towards

those that suffer. I am proud that this government has consistently kept up its

level of overseas aid – even if not all of that ends up in the right hands. But

it’s a sign that we care. And if those among us who are from the EU or further

afield are feeling nervous then as a church we must reassure them and make them

know they are welcome. The bible uses the image of pilgrimage to describe our

journey of faith – we are all pilgrims and strangers in this world, and as such

we should accept those who are among us, especially those who are in the

community of faith, but also all people that we live alongside. The church has

a role in speaking peace and reassurance to white working-class English people

as much as it does to Polish workers and Syrian refugees. And at the very least

we need to pray for the unity of our nation, and that division and hatred won’t

just be covered over but healed.

It’s sometimes been said of

immigrants to the UK, “They don’t belong here.” The question this referendum

has uncovered is ‘Where do we belong?’ Where does our loyalty lie? Who

is in control? Where is sovereignty located – in parliament, in the monarchy,

in Brussels? What exactly does sovereignty mean? The word ‘sovereign’ comes,

ironically from an Italian word sovrano,

which is derived from the Latin super

meaning ‘above’. So a sovereign is a supreme ruler or head. Since the 17th

century the power of the British monarch has been limited by parliament, so

sovereignty has been shared between the 2 institutions. Every international

body that the UK has been part of has involved trading a bit of sovereignty in order to belong to it: The UN, NATO

– both of which can take authority to direct our armed forces in localised

conflict areas – and the EU. Along with sovereignty has been the issue of

democracy.

Ironically the result of the

referendum has put the majority of the country at odds with the majority in

parliament. About 500 out 650 MPs supported the UK remaining. It’s going to be

interesting to see how our sovereign parliament acts to carry out a policy that

it disagrees with. More ironic, to me at least, is the fact that holding a

referendum is not a very British thing to do in the first place. In most

important decisions, such as the vote on same-sex marriage, it was parliament

that decided whereas in Ireland and in France that issue was decided by a

referendum.

So where do we belong? To whom or

to what do we give our loyalty? Who is, or should be, in control?The prophets

in the OT looked forward increasingly clearly to a kingdom that would be

established where God was king. Unlike the empires that came and went – the

Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, Roman Empires (later the British Empire)

– this kingdom would never end. In the dream that K Nebuchadnezzar had, retold

and interpreted by Daniel, this kingdom would be like a rock that filled the

whole earth. And it’s this kingdom that

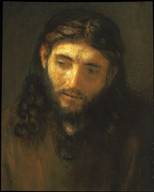

Jesus started to proclaim as soon as he began his public ministry. “The kingdom

of God is near. Repent and believe the good news.” His whole ministry was given

over to proclaiming the kingdom through words and actions: parables, miracles,

exorcisms. And this was a kingdom that was focussed on him – the king of the

kingdom, yet a king who would be rejected, betrayed and crucified. St Paul

writing to the Corinthians says that such a king is a stumbling block to Jews –

who were looking for a heroic messiah to deliver them from the Romans – and

foolishness to the Greeks – who looked for a great philosopher. The writer to

the Hebrews, reflecting on the temporary nature of life on earth, says that

‘here we do not have an enduring city’, and Peter, writing in his first letter

to believers scattered round Asia Minor (modern Turkey) because of persecution,

addresses them as ‘strangers in the world’. When Jesus faced Pontius Pilate,

the representative of the greatest earthly power – the Roman emperor – he said,

“My kingdom is not of this world…You are right in saying I am a king…”

So when it comes to questions of

sovereignty and belonging, to whom do we give our loyalty and allegiance, and

where do we belong. As Christians we must echo Paul’s words when he says, “Our

citizenship (using a Roman term) is

in heaven. And we eagerly await a Saviour from there, the Lord Jesus Christ…”

(Phil 3:20). For me, that means that I don’t get too hung up about earthly

sovereignty. Jesus was prepared to accept the earthly sovereignty of Caesar

when he famously said, “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is

God’s.” The example our Queen gives is the best one as she recognises that we

are all ultimately under the authority of God. She has been scrupulous in

maintaining her constitutional neutrality in the EU

debate, even when The Sun tried to imply her support for the Leave campaign. We

may never know what her personal thoughts have been on the matter. The question

of belonging is important, though. As Christians we belong to a kingdom that

has no geographical borders, whose government is on the shoulders of King

Jesus, whose entry requirements are through a narrow gate, but at the same time

open to all who will pass through that gate – Jesus himself.

One of the complaints about the EU

has always been that it’s full of ‘faceless bureaucrats’, and that it’s

impossible to relate to an MEP because the European constituencies are so big –

the whole of London, for example. The parish system of the C of E locates the

church in a small area that allows us to know who lives here, and them to know

us. When I walk around in my dog collar people, round here at least, know I’m

the Rector (even if they call me Vicar!). Through the local church we can help

people to have a sense of belonging to a kingdom that has no borders, because

it’s the local church that is the ‘shop window’ of that kingdom. I think that

should give us a real mission opportunity – particularly to those who feel that

they are ignored or overlooked by the big structures and institutions.

One of the slogans used by Boris

Johnson and others has been ‘Take back control’. It’s a powerful slogan, but

like most slogans fairly meaningless. As a nation we British don’t like being

told what to do – by our own politicians, let alone by foreigners – even our close

ally the USA. Some years ago Nicy and I took a group from our previous church

to Israel, and I noticed that as soon as British tourists got off the coach

they would scatter and find their own way round, whereas American and Japanese

tourists would stick together, all wearing the same hats and moving round like

a flock of sheep. Who is in control? Is it the UK parliament or the EU

institutions. I wonder how many people have actually bothered to find out how

the EU works, through its elected Parliament, its Council of Ministers – each

from their own member country, through its Commission – a kind of civil

service, or its Court. Some have talked about our independence from foreign

control as we can completely cut ourselves off from the outside world. Well, the

only country that has done that successfully is North Korea. From a theological

viewpoint, the question of control becomes THIS: ‘How much control of our lives

do we allow the Lord to have? There is a danger in valuing independence as a

concept so highly that we put ourselves as individuals at the centre: not

Brussel, not Westminster – it’s up to me what I do. Jesus looks for people who

will allow him to be in control.

We’ve been thinking about wealth

and how we handle money recently. Jesus had a lot to say about it. The EU was

founded as a Common Market to allow trade without tariffs. It would be very sad

and a great shame if we found ourselves locked out of the single market.

Ironically, if we do join the single market again, like Norway, we will still have

to pay a wacking fee and allow free movement of goods, services and labour as

Norway does. The

bible has little to say about

modern international trade and the sophisticated economies of today’s world.

What it does talk about is honesty in selling, not lending at extortionate

rates of interest, not hoarding wealth, and being generous. Where is our

ultimate security? I said earlier that there is much fear around today because

people don’t know what will happen to our economy – on which so much else depends.

All the signs are that in the short-term we will experience a significant

contraction in the economy. And that forces us to consider ‘Where is my

security?’ If my pension fund contracts, if the value of my house goes down or

my mortgage increases where is my faith and trust? And of course that applies

to us as a whole church: since we urge people to give in proportion to their

income, if that income goes down we have to accept that the church’s income

also goes down. This is where we need to trust God, and to encourage one

another.

Finally, where do we go from here?

No-one is quite sure. Never has it been more important to pray for our

political leaders in the UK and EU as they chart a course through new waters.

Using that metaphor let’s pray for our David Cameron in these next few weeks

that he is ‘Captain of the ship’. We need to pray for the civil servants and

others who will spend years now unpicking the 1000s of laws and regulations

that have bound us to the EU – it will be as delicate an operation as

separating Siamese twins. Let’s pray for financial leaders and institutions,

and for foreign citizens who live here and UK citizens who live the EU. And for those who voted to leave because they

feel overlooked, ignored and pushed aside.

We are where we are, and we can

only look forward now – not to a rosy nostalgic past, whether that was the last

40 years in the EU or further back.

Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything, by prayers, with

thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God which

transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ

Jesus.’